Click play for an audio readthrough of this article

Your shoes, kit and environment alter your risk of injury … so does your invisible boob-force.

Injury risk is multifactorial. It’s rare that one thing alone will cause a tear or a strain or a bump or a break. And while women’s bodies, brains and bones play a massive part in injury, non-physical risks are all around us too.

They’re in substandard kit and forces we can’t see. They’re in personality traits we often view as assets.

But through knowledge and better-informed decisions, we can all save ourselves unnecessary time on the sidelines.

The force is strong in you

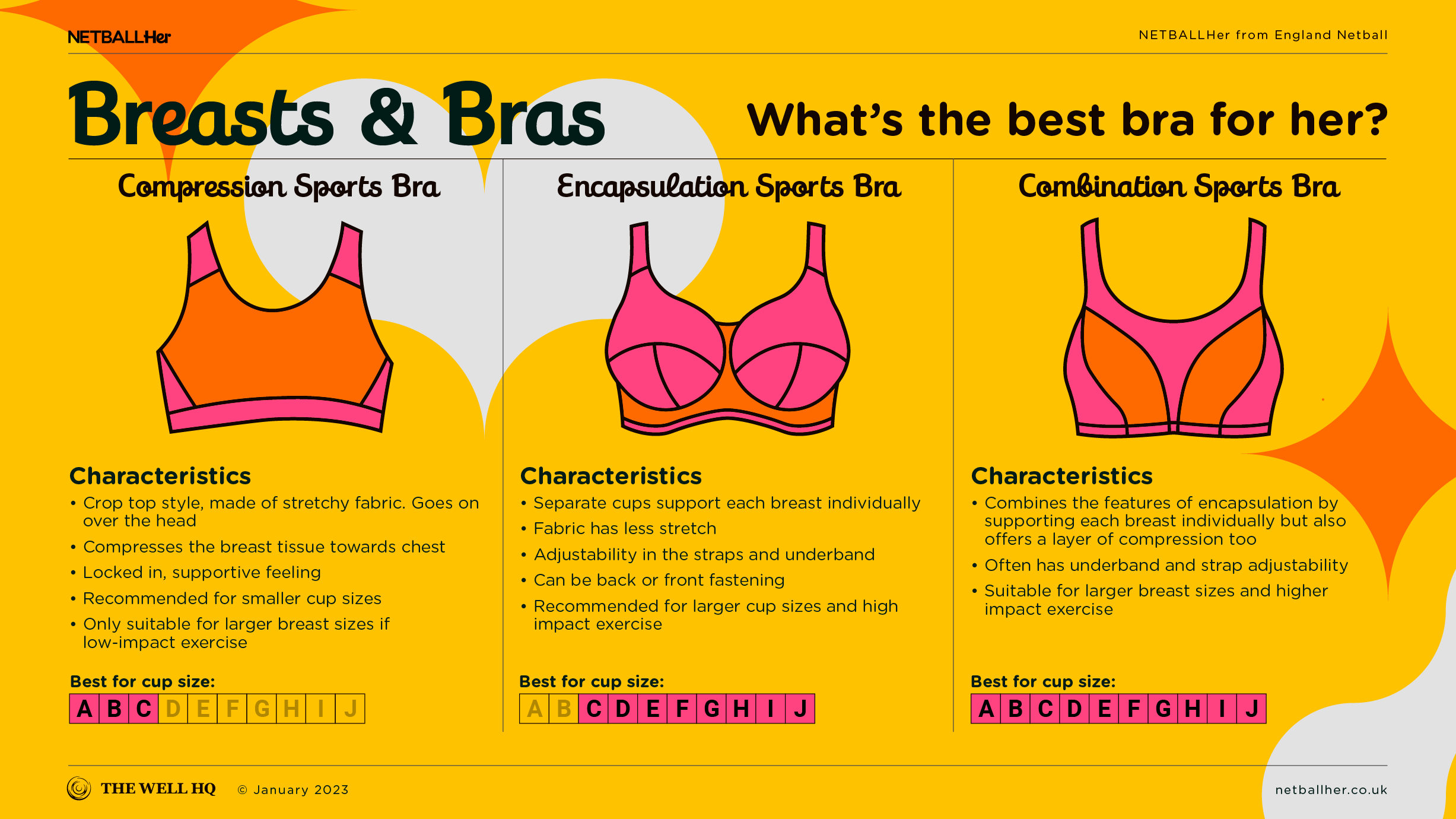

Fact: breasts move when you exercise. Fact: without decent support they create a powerful force of their own.

When breasts move during a run they bounce up and down (accounts for 50% of all movement), side to side (25%) and forward and back (25%).

The bigger the breasts (and the poorer the support) then the stronger the force. This breast force transfers right through the body, all the way to the ground, and itself poses an injury risk as women adapt their technique, often subconsciously, to compensate.

Researchers at the University of Portsmouth found that women with poorly supported breasts counter this force by, among other things, shortening their stride length and breathing differently. Such corrective measures ramp up the risk of injury, yes, but they also lead to early fatigue and significantly impact performance.

Breast injuries

Breast injuries aren’t talked about much. They’re often seen as second-tier injuries and, consequently, they’re massively underreported. Yet breast injuries are common in sport – especially contact games like netball – and more so than you’d realise.

Collision injuries, rubbing, chafing, bruising … in a study of 500 elite female athletes from 46 different sports, 36% said they’d experienced breast injuries and, what’s more, 21% said those breast injuries negatively impacted their performance.

The majority of breast injuries – certainly friction and chafing injuries – are avoidable. Shoulder straps being so tight that they dig into the skin and cause permanent furrows – avoidable. Bras compressing nerves until they cause tingling and numbness in arms and hands – avoidable.

Poor breast support is even associated with musculoskeletal problems in the back, shoulders and neck; manifesting as tension, tightness and pain. This, too, is largely avoidable and, funnily enough, it’s not unknown for doctors to prescribe sports bras to treat such problems.

Speaking of doctors, while there are no extra cancer risks associated with blows to the breast, ‘dead fat necrosis’ (when damaged breast tissue lumps up) can look and feel like the worst news possible. Goodness knows how many women have panicked and / or gone for unnecessary biopsies over the years.

Certainly do always get lumps in your breasts checked by your GP, but also be sure to mention if you’ve experienced a recent or historic blow(s) to the breast during sport.

Solutions to breast injury

Solutions to mitigate breast injuries pretty much all hang around getting a good, well-fitting sports-bra. We’ve known women who’ve tried using plasters or Vaseline or even two bras but most measures are futile when the punchline is this:

You wouldn’t keep using trainers that give you blisters so why wear a sports bra that rubs your skin away?

We’ve a whole section dedicated to sports bras, but suffice to say selecting the right one for you, your breasts, your body shape and your sport is absolutely essential. Get yourself a well-fitting sports bra and you’ll decrease breast motion and friction; you’ll ultimately increase comfort and support.

A well-fitting sports bra is a one-stop measure to boost performance, dial back painful distractions, and counter a whole bunch of unpleasant side-effects.

To the bottom of your sole

We spend most of our sporting lives on them so any pain or discomfort in our feet increases our overall injury risk. And just as too many women are in a badly-fitting bra, too many women are also in bad shoes …

Once again, we have an article dedicated to women’s footwear, but the headline is that choosing the right pair is a) massively and immensely important and b) a bit of a minefield.

Why a minefield? Because most manufacturers will tell you they design sports trainers specifically for the female foot, but that’s not always the whole story.

Men and women typically have different-shaped feet. Women’s heels are narrower, arches higher and the balls of her feet wider. What’s more, these differences tend to be more pronounced the sportier the woman is.

But most sports shoes are diligently and scientifically designed based on the biomechanics of the body attached to that foot. When that body is a man’s (and he’s taller, longer-limbed, stronger, faster and a different shape) then the shoes will simply not be optimised to support women, her feet or her movement.

For cost reasons, many ‘women’s’ shoes start life as men’s moulds. They come off the same production lines with modifications done later … if at all. The problem is that because women’s feet, bodies and movement mechanics are different from men’s – the moulds are fundamentally unsuitable. They contain imperfections and discrepancies that can actually increase a female player’s injury risk.

We’re not necessarily talking about immediate broken toes or ankle snaps, no, injuries may start as innocuously as discomfort, swelling, pinching and pain. Over time, the pain can build and cripple one’s enjoyment of sport, sure, but sooner or later the distractions and pains caused by inadequate footwear can lead to falls, sprains and breaks.

This is because, as we read earlier, inadequate support causes us to – whether consciously or not – compromise on technique.

The solution, like with bras, is to measure thrice and cut once when buying shoes. It’s to ignore marketing slogans and flashy branding and find a pair that works. Try and test multiple options and commit only when you’re sure you’ve found the shoes for you. Make sure they are made for females, and are designed for the high impact nature of netball too.

How women think

It’s never an exaggeration to say that one’s mental state can cause physical problems and that’s as true in sport as it is in life.

Obviously, mental health is a vast topic and we’d never do it justice in one section of one article, so we’ll narrow our focus to just two common places where how we think informs how we approach and play our sport.

Stress

Chronic stress can sharpen one’s injury risk in several ways. Physiologically speaking, stress can lead to inflammation in the body; affecting two key systems: our cognitive functioning and our immune system.

Cognitive functioning. In basic terms, stress can hamper our decision-making. It can cause us to miss a step, or freeze, or mistime, or misjudge, or make a wrong call. When one’s focus or technique fails at the wrong moment, the results can be painful.

On immune function, a stressed-out system will lag in its ability to recover from training and those everyday niggles and pains. Add the fact that chronic stress is like kryptonite for sleep and we risk completely underserving our physical recovery, with each new injury compounding the last one.

There’s a behavioural risk to consider here too. People who are chronically stressed often turn to exercise to cope. On its face, there’s no better way to treat stress, yet over-training can be a real boobytrap.

For example, if you’re feeling stressed and find exercise helps you, you’ll do it more. But if you over-train you’ll tire, be fatigued and further diminish your body’s robustness. Cue more stress, more poor sleep, more bugs in your immune system … and around and round we go.

Perfectionism

It might not seem like a problem, but perfectionism really can be an addictive and self-destructive belief system. If a mantra such as ‘I am what I accomplish and how well I accomplish it’ becomes an obsession then consequences, in all likelihood, aren’t far behind.

In reality, perfectionism is a fear of shame, judgement, blame, and of disappointing others. Research shows that perfectionism ultimately hampers success and puts people on the fast-track to depression, anxiety, addiction and breakdown.

Studies show that women are more likely to exhibit perfectionist tendencies than men and, interestingly, that perfectionism is increasing. Newer generations of young people are demanding more of themselves (and others) than ever before. Note that today’s form of perfectionism is more about what others think of us than it is a desire for self-improvement …

It’s a fascinating area of study but for our purposes, guess what?

That’s right – perfectionism can increase your injury risk.

For one, perfectionism is often incompatible with being vulnerable or at least showing vulnerability. There’s often an unwillingness to ask for help or admit weakness of any kind. Translated in injury-talk, this is when a niggling pain is ignored. It’s when she trains through something that needs a doctor’s eye. It’s when small injuries become big problems.

There’s also self-punishment. Let’s say an active woman has an injury and needs some at-home DIY physio to recover. With her perfectionist all-or-nothing mindset, she’ll diligently follow her physio regimen until, for whatever reason, she misses a day.

Life’s just like that sometimes … but a perfectionist will overly punish any self-perceived failings. She could easily descend into a spiral of negative self-talk centring on her lack of strength, drive and commitment.

From here, our injured perfectionist will likely follow one of two paths: 1) She’ll think it’s all pointless, give up entirely and delay her recovery. 2) She’ll overcommit to make up for lost time and risk aggravating the injury.

The fact is that many women think they can do it all. We like to be superwomen and we demand nothing but the best from ourselves. That can be a strength, but only to a point. Vulnerability and asking for help are often the best things we can do for ourselves.

Researchers from the Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences and the University of Portsmouth recognised how useful vulnerability can be in sport. Having the courage and capacity to share experiences and shortcomings is a real psychological strength, while asking for help – knowing when to share, with whom, and to what extent – are huge plusses for any athlete, any coach, any team.

Equipment and facilities

First equipment and you’re probably noticing a pattern here. Not everything is designed for women. In fact, let’s go further. Most things are designed by men for men, and women are expected to make do.

That extends to gym equipment too. Throughout this injury section we encourage women to engage more in strength training to condition the body well. But if strength training means lifting weights then beware that the benches and machines at your gym mightn’t be optimal for you. Not by default, anyway.

The height and length of a weight bench may be such that a woman’s feet can’t reach to be flat on the floor. This is the ideal and without it your technique and form will suffer. Should you come up against this issue then find and use yoga blocks or place weight plates under your feet to get into the correct position.

Yes, these are quick and dirty fixes … but we can’t wait around for the fitness industry forever.

Now facilities. In sports like football or rugby, playing surfaces add another dimension to injury risk for female players. Women’s teams are often relegated to poorer playing surfaces, or artificial playing surfaces, or are moved randomly between the two. They’re often at the mercy of the men’s team’s schedule. This all contributes to injury risk.

It mightn’t seem like this applies to netball, but we too need to be very mindful of the playing surface and how it amplifies injury risk.

A netball court is hard and unforgiving. Of the injury risks outlined in this whole section, the majority are amplified when you factor in a solid surface. Simply playing where we play makes it all the more vital netballers condition our minds and bodies for optimal movement and technique – always.

As a reminder, the content of the course belongs to The Well HQ. You have permission to access and use the content yourself or, if you are an organisation, for the number of users selected, but are not otherwise permitted to share such content with others, all in accordance with our Course Terms and Conditions.