Click play for an audio readthrough of this article

Considerations, complications and stumbling blocks for active women planning pregnancy

Some of the topics covered on NETBALLHer do get press these days, certainly compared to five, ten or twenty years ago. We hear more and more about female injury (particularly ACLs), kit (especially white shorts), and menstrual cycles (albeit the info’s often wonky) …

This, we can almost certainly call progress. However, there’s a major and noticeable hole in the female sport conversation … and its name is fertility.

There are just so many considerations for active women planning a family. For starters, there are multiple ways to become a parent and all options have their challenges. Then there’s the timing: the annoying truth is that one’s fertile years and their athletic peak pretty much coincide so there’s bound to be tough decisions and sacrifices either way.

Many athletes and active women decide to wait until their career ends to start families but another truth is that the potential for complications increases with age and many don’t start exploring options until there’s fewer of them.

We all want to believe the fairytale of pregnancy … but for female athletes it’s rarely so simple.

The parent gap

There are plenty of examples of top athletes who’ve taken time out to have a child before returning to sport and winning ways. So yes, if we want to read about the isolated experiences of Serena Williams or Jess Ennis-Hill – or netball’s own Ebony Usori-Brown – we can all find that information …

However, fertility, motherhood and the whole parenting topic has yet to filter into a comprehensive or overarching piece of governance or best-practise for sport, and it doesn’t help that these areas are still under-represented in academia.

Some sports bodies have taken the initiative themselves, which is a big step forward, but still active women are quick to specifically point to fertility as a gaping hole in their knowledge.

The culture around pregnancy is a little squiffy too: many professional athletes avoid talking with coaches and club doctors on this issue for fear it’ll compromise their standing or team selection. This silence preserves the hush. It limits progress.

Menstrual myths

The topic of fertility in sport – and for active women in general – tends to overlap with some of the common, faulty wisdom around the female body.

For example, many sporting cultures promote the loss of the menstrual cycle as some kind of optimum. It’s not. Fairly obviously, losing the menstrual cycle and periods isn’t going to help you get pregnant now, but doing so can impede your chances later, too.

The menstrual cycle isn’t (or shouldn’t be) a switch that’s activated and deactivated. The body goes through serious stress in the deactivation process as it compensates and adapts to an unhealthy, abnormal new normal.

There are physical and psychological side effects when the menstrual cycle disappears and it can be hugely difficult to bring things back online. If an active woman has spent any time in the cycle off position, getting pregnant could be a real trial. She could face a monthslong or even yearslong journey before she’s anywhere near being ready to conceive or grow a baby.

Bodyfat

Underfuelling issues are often mixed up with further iffy messages around bodyfat. In some corners of sport the prevailing wisdom is that thinner is better, and <12% bodyfat is some kind of stretch goal.

In a sporting context this info is jarring and probably a fast track towards RED-S. In the context of fertility it’s problematic in a couple of directions, but mainly because the female body stores reproductive hormones within body fat.

In plainer terms, women need some body fat to conceive.

Even if she has a menstrual cycle, an active woman with a very low bodyfat ratio could be on the back foot from the get-go should she want to get pregnant.

Hormonal contraception

Hormonal contraception (HC) can be a muddy area when talking fertility.

Estimates put the percentage of active women on HC at around 60%, increasing to roughly 66% in female athletes in their twenties.

The most common form of HC is the pill and beyond contraception, some key reasons for taking it are to manage premenstrual and menstrual symptoms: to make things more predictable; reduce period pains and / or stop periods altogether.

These are all perfectly valid reasons, yet too often the decision to use HC is based on incomplete information, and women on it may lack knowledge as to what their menstrual cycle is and isn’t.

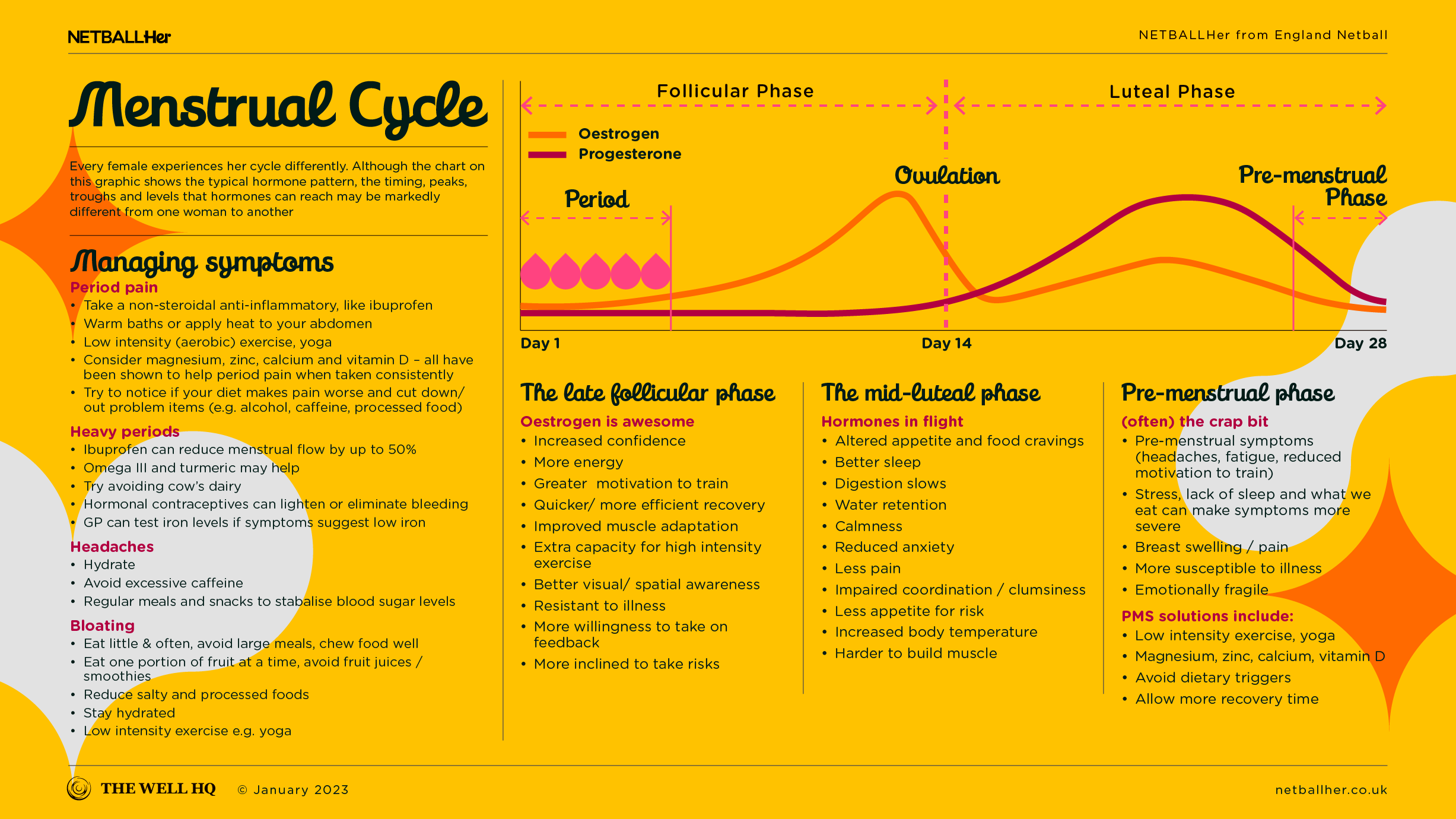

We’ve lots of content dedicated to this over on our Menstrual Cycle section, but the key piece of info is that some forms of HC involve a monthly bleed that is not, repeat not, a proper period. It’s not a menstrual cycle but part of what we call a pill cycle.

Why does this matter? Because a consistent monthly period is a solid way to track health. If a menstrual cycle is inconsistent, disruptive or triggers excessive symptoms it’s often a sign that something isn’t right and a cue to go get checked out.

Thus women on HC may be flying blind as to how good (or not) their reproductive machinery is. Should such a person wish to conceive, it mightn’t be as simple as just coming off the pill. There may be other checks and treatments to go through that’ll require time and patience.

If she’s still in her playing window then unforeseen delays and complications may force big decisions on her sporting / parenting future.

Meet Geva

England netballer Geva Mentor recently spoke up about her experiences managing long-term oral contraception in the national press and recommends women on HC get their fertility checked every three or four years. Geva also took the decision to freeze her eggs at the age of 35 because a female’s egg quality declines with age, as does the possibility of being able to get pregnant.

“It shouldn’t be seen as something you HAVE to do because you’re old and you’re single,” said Geva. “I believe it’s something that you SHOULD be able to do for yourself. You might want to continue your playing career while you still can.”

We can all be inspired by Geva. She did her homework, talked to the right people and sought ongoing support. She had good information and put a plan together, with some inbuilt insurance that she could largely stay in control and in charge of her own destiny.

It’s so refreshing to read Geva’s story. Many sports women don’t know what they don’t know. And they feel much too uncomfortable to even start the conversation.

Conclusions?

There aren’t any, really. We offer some considerations (as above) but pregnancy is such a personal thing and it depends entirely on what you and / or your partner want. It depends on who you are and where you’re at.

Pregnancy / fertility and sport don’t make the best bedfellows, and the lack of awareness, knowledge and even conversation is limiting this topic going mainstream. It has spent so long in the darkness, just bringing it out into the sunlight is the A-1 goal for now.

In terms of knowledge, there are things to look at and be aware of. There are trailblazers we can look up to. But there’s no neat little bow we can wrap around it.

Instead, all of us can try to open up the conversation, break the taboos and be mindful of the under-appreciated variables (culture, RED-S, bodyfat, HC) to consider at the start of one’s fertility journey. Oh and naturally we’d ask active women considering starting a family to pick up conversations with trusted medical advisers as soon as possible.

England Netball are further ahead than most in looking at pregnancy and postnatal care, so please contribute to that evolution by sharing this article and reading more in the Pre & Postnatal section on NETBALLHer.

As a reminder, the content of the course belongs to The Well HQ. You have permission to access and use the content yourself or, if you are an organisation, for the number of users selected, but are not otherwise permitted to share such content with others, all in accordance with our Course Terms and Conditions.