Click play for an audio readthrough of this article

Netball’s increasing popularity is great for the game, but more players means more injuries unless better knowledge and strategies are in place.

Active women are more likely than men to pick up injuries – certainly specific types of injuries. And in a game composed of running, jumping, jerking, bumps and collisions, netball carries a higher level of risk than many other sports.

The vast majority (between 57 and 86%) of all netball injuries occur in the lower limbs, and knee trauma represents almost one-third of all netball-related hospitalisations.

Injury is more likely in women (than men) for several reasons but, in truth, the world still needs to learn a whole lot more in this area. That said, there is a solid knowledge base – and lots of emerging evidence – about injuries, risks and her.

So here are some of the more common injuries in netball before we cover how you can reduce your risk.

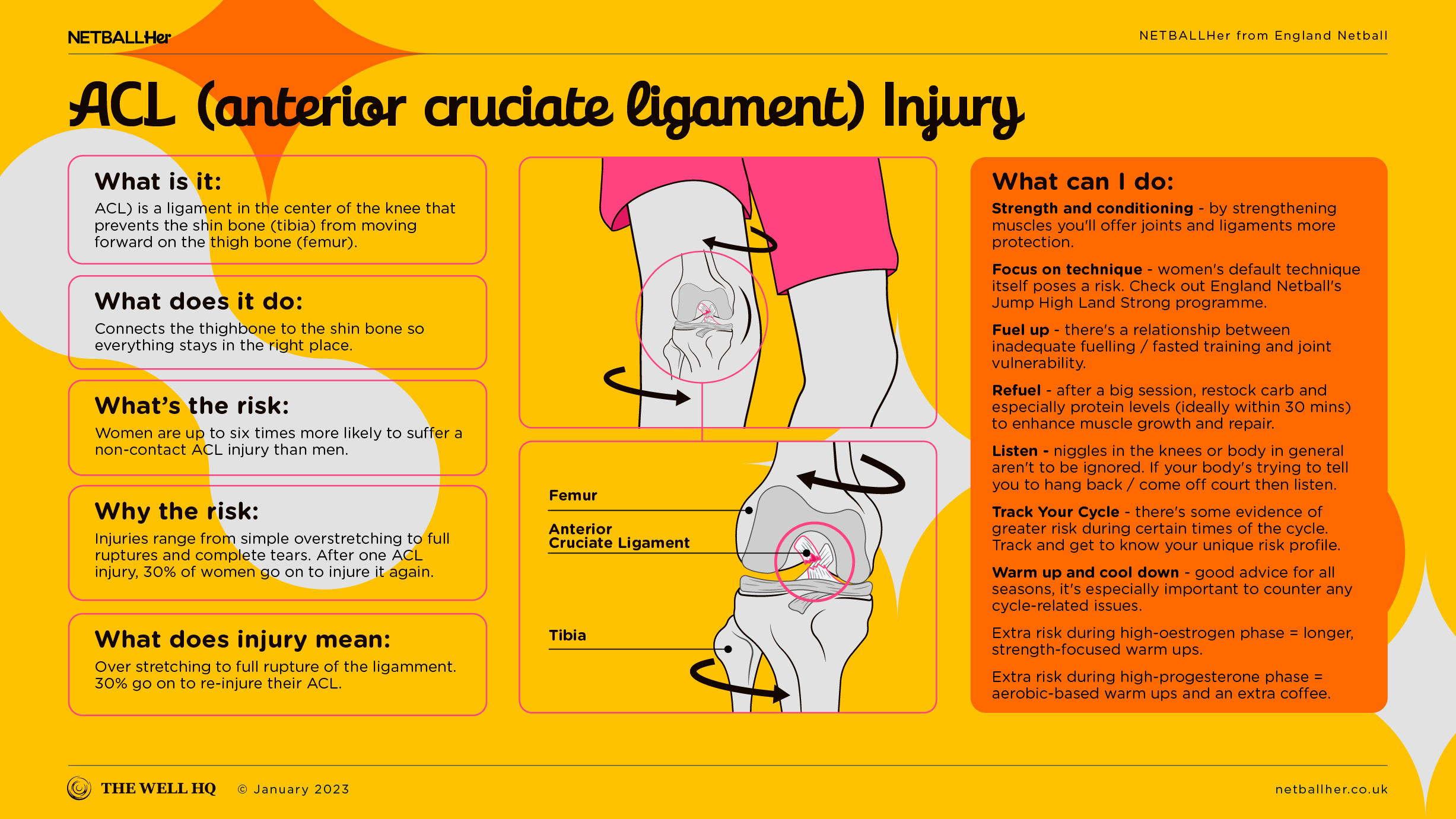

ACL

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the better-known ligaments in the human body, owing to high-profile injuries in other women’s sports like football, netball and hockey.

A recap: the ACL is one of two cruciate ligaments (strong bands of tissues) in the knee, which make a cross formation at the knee’s centre. Along with the collateral ligaments, which run down each side of the knee, the ACL connects the thighbone to the shin bone, and it controls and stabilises the knee joint.

It’s an essential piece of kit, the ACL, yet women are up to six times more likely to suffer a non-contact ACL injury than men. And injury can mean anything from a sprain to a partial tear, a complete tear, or an avulsion – when it tears away.

We know that ACL injuries are most common in sports that involve sudden stops, changes in direction, jumping and landing. Netball, then.

Pain

A major factor in women’s higher risk of lower-limb injuries (including ACL injury) is our anatomy.

Basically, women have a wider pelvis, on account of sometimes needing to push a baby through it. Wider hips means a bigger angle between our hips and knees than in a man’s body. This means greater angular stress goes through the knee as we move and it majorly affects how we jump, land, turn and and move. You can read more in this article, but women and men’s natural techniques differ, and these differences are especially apparent in netball.

The typical man changes direction and lands jumps on his toes. He also bends his knees to absorb impact. The typical woman lands on flat feet with a straighter leg with her knees often caving inwards. His way gradually absorbs shock, strain and impact into the muscles. Her way invites shock, strain and impact into the bones and joints.

Women’s technique here heightens the risk of serious injury, and it also causes joint pain, whether it’s intermittent or constant. Whilst there’s nothing we can do about our skeleton, there is lots we can do about how our bodies move.

We can intentionally and deliberately re-wire how our nervous system coordinates our muscles, and develop a new technique of balanced, coordinated and stable movements. This can and will significantly reduce our risk of lower limb injury.

England Netball have developed the Jump High, Land Strong programme to help coaches and players perform these injury-risk-lowering conditioning movements as part of a warm up.

Finger & hand injuries

Finger and thumb injuries, as you’ll probably know, are amongst netball’s most common. There’s the immediately obvious staves and breaks, but netballers need to be particularly wary of dismissing finger injuries by saying: “I’ve only jarred it.”

Hurt fingers can leave a significant weakness in the finger and lead, potentially, to worse injury later. We need to be cognisant of fractures and dislocations, sure, but there’s also the possibility of torn ligaments, tendons, and muscles in the hand.

The pain of a hand injury is one thing. Its impact on your netball game is another. And the negative impact of being without the use of a finger, thumb or whole hand can be a different ball game altogether.

You’ll probably know the ordeal it is trying to struggle through a game with an aching hand or finger. It can be excruciating. Yet because it’s such a small part of the body, netballers commonly try to play through the pain of a finger or hand injury, often giving themselves a hard time for not being tough enough …

But the longer you leave a finger or hand injury, the more you risk compounding the damage thus the longer your time on the sidelines may be. We rely on our hands for netball – and so much else in life – so it pays to stay with caution. Don’t be a hero. Don’t risk turning a two-weeks-out-bad into a two-months-out-worse.

Concussion

A concussion is usually caused by a blow to the head. In a game where knocks, trips and bumps are the norm, concussions definitely should not be dismissed.

A concussion is considered a mild traumatic brain injury. When the head withstands a jolt from external forces (hitting the floor, glancing off another player, being shoulder barged), the brain moves around in the skull. As the brain moves, it twists, contorts and bashes against the skull bone. All of this causes brain cells to get damaged to the point they, at least for a short time, don’t work properly. Hence why concussions can impact our balance, co-ordination and memory. Other symptoms include headaches and migraines.

Research shows that women and girls are more susceptible to sport-related concussions than men, and that women’s concussion symptoms last longer – hence a longer recovery time.

Because women have weaker necks than men, we often don’t have enough strength to withstand the external forces which pose danger to the brain, and it’s harder to hold our heads off the floor during a fall. Also, women’s brain cells are longer and thinner than men’s, making them more susceptible to damage when the brain is rattling around the skull.

In 2023, the UK Government issued new guidelines for recognising concussion, and returning players safely to work and sport in the weeks and months following a concussion. In a study of high school sport in America, it was found that girls were less likely to be removed from the field of play following a suspected concussion than boys, yet research shows that if coaches and officials are better able to spot concussions – and signs and symptoms of brain injury – then more concussions will be picked up and treated safely and appropriately.

Concussions usually (though not always) carry symptoms, making them easier to spot. But a growing body of research suggests it’s the less obvious head-knocks we need to watch for. Read much more here.

Sub-concussion

Sub-concussions are blows to the brain that fall below the full concussion threshold. They’re not bad enough for the full-fat label, but that’s a problem. A sub concussion is when about a quarter of the force required for a concussion is absorbed by the brain. As such, players will likely shake off a knock, a fall, or a bash to the head, and carry on playing.

This means that sub-concussions can happen multiple times during 60-minutes. Colliding bodies, falls to the ground, shoulder barges, body blows, accidental whacks… it’s not just direct contact to the head we need to watch for, but bumps and blows which put excessive forces through the whole body. These forces often end up impacting the head and the brain, particularly in causing the brain to twist and rotate within the skull.

If a player consistently suffers sub-concussions, the low level damage of each event starts to accumulate, because there is not enough time between events for the brain to recover. This accumulation of trauma leads to inflammation in the brain, and this inflammation then triggers the build up of proteins that are also seen in the brains of people with neurodegenerative disease.

The condition is called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), which can manifest as difficulty in thinking and managing emotions, to mental health problems and even early onset Alzheimer’s and dementia.

There’s no cure for CTE and, from what we’re learning, it may be an important new frontier in women’s sport / medical research. As you might have guessed, we explore concussion and sub-concussions, and how to take a preventative approach to brain health in netball in this article.

Breasts

Breasts move during exercise – we explain more in our Bras & Kit section. But basically, moving breasts create a force which transfers through the body right down to the ground. Breast movement changes our whole movement mechanics during sport. Hence why, without a good sports bra, the risk of general injury – not to mention pain and discomfort – is higher.

But it’s odd we tend not to talk about breast injuries themselves when they’re actually pretty common. In a study of 500 elite female athletes from 46 different sports, 36% reported experiencing breast injuries and 21% believed the injury hurt their performance.

Breast injuries can include rubbing and chafing right through to contact injuries (often a result of bumps and knocks) which can cause significant issues.

For one thing, a contact breast injury can mean acute pain. But injury to the breast can damage the tissue and cause what’s called ‘dead fat necrosis’. Dead fat necrosis (damaged or dead tissue) can lead to lumps in the breast that may be mistaken for breast cancer.

Best say it now: breast injury does not increase a woman’s risk of breast cancer, but the appearance of a lump or lumps can be hugely alarming and prompt women to get checked, or and even undergo a biopsy unnecessarily. Protecting breasts during sport is overlooked, but some innovation is emerging in this area, for example, ‘Boob Armour’ inserts to protect tissue during sport.

Menstrual cycle and injury

This isn’t an injury as such but something to be mindful of. The menstrual cycle has been implicated in injury. This is an emerging area of research, and we still don’t know for sure how important the hormones of the cycle are in terms of injury risk.

Nonetheless there is evidence that in the second week of the cycle (known as the late follicular phase), injury prevalence is slightly higher than at other times.

We also know that menstrual cycle hormones can have a knock-on effect on things like risk-taking, concentration, coordination, hydration and pain signalling. All of these could have a bearing on injury and its risk factors.

At the moment, it’s best to take an individual approach. Some women notice they get niggles that flare up or tightness that appears at certain times of the menstrual cycle. It’s great to note this down in cycle tracking, because then you have a much clearer idea of whether flare ups are indeed related to your cycle, and you can proactively manage that.

Clubs are now increasingly detailing the time of a player’s cycle when she presents an injury, and this is a positive step. Over the longer term this’ll allow for clubs to determine whether or not players’ menstrual cycles correlate with injury prevalence.

But we’d also ask you to bear in mind that injuries are complex things. Multiple factors play a part and the menstrual cycle alone doesn’t cause injury. What we’re talking about is whether it may, in some women, be a contributing factor.

We detail the relationship between the menstrual cycle and injury in more depth here.

… and talk injury strategies and risk-reduction here. See you there.

As a reminder, the content of the course belongs to The Well HQ. You have permission to access and use the content yourself or, if you are an organisation, for the number of users selected, but are not otherwise permitted to share such content with others, all in accordance with our Course Terms and Conditions.